First, William Herebert's 14th-century version of the Christmas hymn, 'Christe redemptor omnium' (for the Latin text see this page).

Cryst, buggere of alle ycoren, the Fadres olpy Sone,

On toforen ey gynnyng boren over alle speche and wone.

Thou lyht, thou Fadres bryhtnesse, thou trust and hope of alle,

Lust what thy folk thorouout the world to thee byddeth and kalle.

Wrouhte of oure hele, nou have in thyne munde

That of o mayde wemles thou toke oure kunde.

Thys day berth wytnesse, that neweth uche yer,

That on alyhtest from the Fader, of sunne make ous sker.

Hym hevene and erthe and wylde se and al that ys theron,

Wrouhte, of thy comynge, hereth wyth blisfol ron.

And we, nomliche, that beth bouht wyth thyn holy blod

For thys day singeth a neowe song and maketh blisfol mod.

Weole, Louerd, beo wyth thee, yboren of o may,

Wyth Fader and the Holy Gost withouten endeday. Amen.

(Christ, buyer of all chosen, the Father's only Son,

One before the beginning born, above all speech and wone.

Thou light, thou Father's brightness, thou trust and hope of all,

Hear what thy folk throughout the world to thee pray and call.

Author of our salvation, have now in thy mind

That of a maid sinless thou took our kind. [nature]

This day bears witness, which renews every year,

That one alights from the Father, from sin to make us sker. [clean, pure, bright]

Him heaven and earth and wild sea and all that is therein,

Author of thy coming, praise with joyful song.

And we, especially, who are bought with thy holy blood

For this day sing a new song and make joyful mod. [celebrate with glad hearts]

Glory, Lord, be with thee, born of a may, [maid]

With Father and the Holy Ghost, without an ending day. Amen.)

A few highlights of the language: 'olpy' in the first line might look like a mistake for 'only' but is in fact a distinct word, descended from Old English 'anlipig', which means 'single, sole, unique', a good way of translating the Latin unice. I always like Herebert's translation of auctor, 'creator, maker', into English as 'wright' (as in 'playwright'); and sker is also a nice word, from Old Norse skærr, 'bright, pure'; hence the old name for Maundy Thursday, Sheer Thursday.

This is a particularly fluent and confident translation, with a lovely swing in the rhyme and rhythm. It's also a poem which neatly manages to describe its own beauties, because song and singing and the delight they express are central to this hymn. It says that at Christmas all creation expresses its pleasure at Christ's coming in joyful song ('wyth blisfol ron'); heaven and earth and the wild sea sing ('wild' is Herebert's addition - isn't it great?) and we sing, too: 'singeth a neowe song and maketh blisfol mod'. The allusion here is to the psalm sung on Christmas Day: 'Sing to the Lord a new song; sing to the Lord, all the earth'.

The song is 'new' because Christ's coming gives new life and new meaning to everything in the universe; but Herebert's song is 'new', too, because it's a new rendering of an old hymn (already at least six hundred years old by Herebert's day). A translation is always a process of renewal, of adding something new. The Latin hymn has some beautiful lines about the recurring observance of the Christmas feast, which returns every year to call the mind back to Christ's entrance into the world:

Hic praesens testatur dies,

currens per anni circulum,

quod a solus sede Patris

mundi salus adveneris.

(This the present day testifies,

turning in the circle of the year,

that one alone from the Father's seat

comes forth for the salvation of the world.)

Herebert renders this:

Thys day berth wytnesse, that neweth uche yer,

That on alyhtest from the Fader, of sunne make ous sker.

(This day bears witness, which renews every year,

That one alights from the Father, from sin to make us sker.)

Herebert translates the verb testatur ('bears witness'), and he retains the important tense of the verse ('alights', not 'alighted'), the present tense which suggests that Christ's coming is not only an event which happened far back in the past but something which recurs each year, in the eternal now of liturgical time. But Herebert adds a new idea, too: the day, he says, neweth every year, and this word suggests not only the newness and nowness of the Christmas feast - that every year it happens now, anew - but also its rejuvenating power, because in Middle English newen suggests renewal, new growth, rebirth, regeneration. Just as Christ's entry into human time brought a new kind of life, once and for all, so Christmas, recurring each year with the turning cycle of nature and the liturgy, brings a renewal of that life - a fresh start, a time of new beginnings.

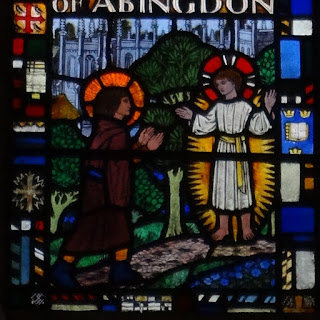

'Christe redemptor omnium', with Old English gloss

(BL Cotton Vespasian D XII, f. 34)

This idea of renewal and the cycle of the year is linked, of course, with the fact that Christmas and the New Year fall so close together. In the north the cusp of December and January is a time of seasonal and cosmic rebirth; with the solstice we passed the darkest midpoint of winter, and now spring is in sight. Although historically there have been various ways of reckoning when the New Year began - different kinds of legal, liturgical, and bureaucratic calendars had their own dates, from the first Sunday of Advent to Lady Day in March - the idea that Christmas or 1 January was the beginning of the new year was always around somewhere throughout the medieval period, and the hymn's reference to the cycle of the year (per anni circulum) might have suggested to Herebert this wider context of the day which neweth - which brings renewal and new birth.

I think there may be a further play on words here, too, because to a fourteenth-century ear neweth might also have suggested the word 'Nowell'. In medieval England Nowell was both a name for Christmas and a greeting used to acknowledge the season (as in 'The first 'Nowell!' the angels did say...'). It was common in Anglo-Norman in Herebert's day, though it isn't recorded in English until the end of the fourteenth century; Herebert certainly knew Anglo-Norman, and this might have added a little something extra to his choice of word here. The etymology of nowell is ultimately from Latin natalis, via French (noël, of course), but once it became a Christmas greeting English poets liked to play with some of the cross-linguistic possibilities offered by this word. It was very common in the refrains of carols, and so, for instance, one fifteenth-century carol has some punning fun with Nowell and the phrase 'Now is well':

Now is well and all things aright

And Christ is come as a true knight,

For our brother is king of might,

The fiend to fleme and all his. [to put to flight the devil and everything belonging to him]

Thus the fiend is put to flight,

And all his boast abated is.

Since it is well, well we do,

For there is none but one of two: [no choice but one of these two]

Heaven to get or heaven forgo;

Other means none there is.

I counsel you, since it is so,

That ye well do to win you bliss.

Now is well and all is well,

And right well, so have I bliss;

And since all thing is so well,

I rede we do no more amiss. [I advise we sin no more]

(This is a version in modern spelling; here's the Middle English from E. K. Chambers and F. Sidgwick, Early English Lyrics (London, 1921), p. 177. The source is Oxford, Bodleian Library Eng. poet. e.1.)

William Herebert would have liked that image of Christ as a 'true knight'. In the one surviving manuscript this carol doesn't have a refrain, but we could imagine it being sung with a lively 'Nowell!' refrain like this medieval carol, or perhaps this one:

With such a refrain the repeated cry of 'Nowell!' would pick up the verses' emphatic assertion that Christ's coming means that 'now is well', and the only possible response therefore is strive to live virtuously, to 'do well'. It's funny what associations a little word like 'well' can conjure up: you might think of Julian of Norwich, and 'all shall be well', or of Piers Plowman and the quest to find out what it means to 'do well' - a kind of perpetual New Year's resolution.

More kinds of wordplay on Nowell are possible too. Other carols pun on the echo between Nowell and news, which is a resonant word in the context of Christmas with its repeated stories of annunciation (to Mary, to Joseph, to the shepherds, to the magi...), the delivery of the 'good news' of Christ's birth. The carol in the video above uses both 'nowell' and 'tidings' to describe the message of the angel to Mary, and both might also be called news. I talked about 'tidings' and the idea of Christ's birth as brand-new and surprising 'news' in carols here.

And then there's that link between nowell and new, emphasising the idea of Christmas as a time of renewal. Early in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, when Arthur's court are feasting at Yuletide, there's a delicate bit of wordplay on new/Nowell:

Wyle Nw Yer watz so yep that hit watz nwe cummen,

That day doubble on the dece watz the douth serued.

Fro the kyng watz cummen with knyghtes into the halle,

The chauntré of the chapel cheved to an ende,

Loude crye watz ther kest of clerkez and other,

Nowel nayted onewe, nevened ful ofte.

(When the New Year was so young that it was newly come,

That day the company were served double portions on the dais.

When the king was come with knights into the hall,

The chanting in the chapel having come to an end,

Loud cries were uttered there by clerks and others,

'Nowell' repeated anew, named again and again.)

Nowell is echoed in onewe, suggesting a scene of busy, cheerful noise: everyone is calling out 'Nowell!' to each other in celebration of the season. It's Christmas they've gathered to celebrate, but by the time of this feast - which is about to be dramatically disrupted by the Green Knight - it's apparently New Year's Day. We're told that the New Year is still very new, in its first youth and freshness - the year is described as yep (pronounced 'yeap'), a lovely word for someone young, lively and energetic. A few lines later the same word is used to characterise the youthful King Arthur himself:

Bot Arthure wolde not ete til al were served,

He watz so joly of his joyfnes, and sumquat childgered:

His lif liked hym lyght, he loved the lasse

Auther to longe lye or to longe sitte,

So bisied him his yonge blod and his brayn wylde...

Therfore of face so fere

He stightlez stif in stalle,

Ful yep in that Nw Yere

Much mirthe he mas withalle.

(But Arthur would not eat until all were served;

He was so merry in his youthfulness, and somewhat boyish.

He liked to take life lightly; he loved the less

Either to lie around or sit still too long,

He was so stirred up by his young blood and his wild brain...

So with a proud countenance

He stands masterful in the hall,

Very yep in that New Year,

Much mirth he makes withal.)

It's the youth of the year, and at the time of the poem Arthur's court too are in the flower of their youth - we're told that 'all was this fair folk in their first age'. Every reader of this poem would know what a tragic end that court would have, how its flower would fade and the fellowship of the Round Table would fall; but the poem captures them all when they're young and yep, beautiful and merry and a little wild. All the important things in Gawain happen during the Christmas season, and the Yuletide setting of the poem is vividly brought to life throughout - in the bleakness of Gawain's winter journey, the jollity of the court's celebrations, the warmth and intimacy of fireside feasting. Somewhere behind this, although difficult to pin down, is probably a myth of seasonal rebirth - a ritual death of the old year, perhaps, like the Green Knight who springs back to life when his head is cut off.

Gawain and Arthur at the feast (BL Cotton Nero A X, f. 94v)

But as poor Gawain learns, the promises you gaily make in the first flush of Yuletide celebrations eventually have to be put to the test as the year runs on in its course:

This hanselle hatz Arthur of aventurus on fyrst

In yonge yer, for he yerned yelpyng to here...

Gawan watz glad to begynne those gomnez in halle,

Bot thagh the ende be hevy haf ye no wonder;

For thagh men ben mery in mynde quen thay han mayn drynk,

A yere yernes ful yerne, and yeldez never lyke,

The forme to the fynisment foldez ful selden.

Forthi this Yol overyede, and the yere after,

And vche sesoun serlepes sued after other...

(This pledge of adventures Arthur had at the beginning

Of the young year, for he ever yearned to hear bold words...

Gawain was glad to begin that game in the hall,

But if the end be sorrowful, do not wonder at it:

For though men be merry in mind when they have drunk well,

A year runs very swiftly, and yields never the same again;

The beginning and the end rarely accord.

So this Yule passed, and the year that followed,

And every season in its turn succeeded one after another...)

The year goes round, and Gawain has to fulfil his promise to the Green Knight when Yuletide comes again. Young Gawain grows wiser through testing and temptation, and learns more from failure than from success - there's a comforting thought, if you find making New Year's resolutions as daunting as I do!

January (BL Royal 1 D X, f. 9)

In our own times New Year is a stand-alone secular celebration, so distinct from Christmas that some people go back to work in between the two dates and pack their decorations away before New Year's Eve; but that wasn't the case in the Middle Ages, where both were part of Yuletide and the Christmas season was a more organic whole. In the world of Gawain, the words Nowell and Yule and New Year are all very closely linked (a kind of alliterative concatenation, almost). When the Green Knight enters he brings Christmas, Yule, and New Year - and yep - all together as the occasion for his challenge to the court:

I crave in this court a Crystemas gomen,

For hit is Yol and Nwe Yer, and here ar yep mony.

(I demand in this court a Christmas game,

For it is Yule and New Year, and here are many yep men.)

Some medieval carols, similarly, treat Yule and New Year as essentially synonymous:

Now is Yule come with gentyll cheer; [excellent fun]

In mirth and games he has no peer,

In every land where he comes near

Is mirth and games, I dare well say.

Now is come a messenger

Of your lord, Sir New Year,

Bids us all be merry here

And make us merry as we may.

Since the late 20th century it's become common to invert the traditional relationship between fasting and feasting in the Christmas season. The ancient custom was to fast in Advent in preparation for the feast, and then to celebrate for at least twelve days after Christmas (and to some degree, all through January). Now we do it the other way around; for many people the feast is followed by a penitential fast, in the form of 'Dry January' or New Year's resolutions about eating less and going to the gym. As a manifestation of the desire for a fresh start, this 'New Year, new you' impulse is natural enough, but it does strike me as strange that it's so often framed in negative terms. There's an odd sense, encouraged mostly perhaps by journalists and advertisers, that the indulgence of Christmas is a 'sin' which has to be atoned for - as if eating and drinking with friends and family, to celebrate the turn of the year from darkness to light, is a moral lapse for which one must subsequently make amends by privation and self-punishment. We are much less kind to ourselves in these weeks after Christmas than the strictest confessor would have been in the Middle Ages. Feasting at Christmas is not something to atone for, but a proper observance due to the season; and that feasting is also the sustenance we need to carry us into the New Year with energy and strength. The renewal of Nowell in these medieval poems is not a repudiation of Christmas feasting, but the power and life with which Christmas endows us as the new year begins. Find something new in the New Year, certainly, but don't punish yourself for enjoying Christmas first! Sing a new song, seek new adventures; it's true that 'a yere yernes ful yerne, and yeldez never lyke', and we don't know what it will bring. But nevertheless: 'Now is well and all is well'.